Charity Case

By JIM HARMON

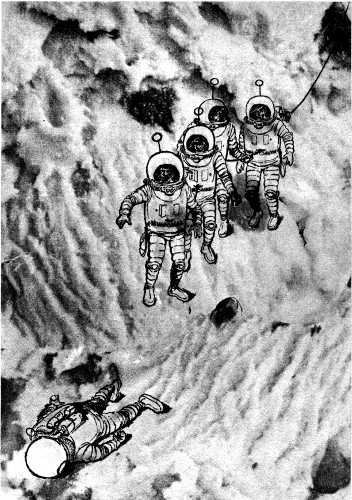

Illustrated by DICK FRANCIS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction December 1959.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Certainly I see things that aren't there

and don't say what my voice says—but how

can I prove that I don't have my health?

When he began his talk with "You got your health, don't you?" it touched those spots inside me. That was when I did it.

Why couldn't what he said have been "The best things in life are free, buddy" or "Every dog has his day, fellow" or "If at first you don't succeed, man"? No, he had to use that one line. You wouldn't blame me. Not if you believe me.

The first thing I can remember, the start of all this, was when I was four or five somebody was soiling my bed for me. I absolutely was not doing it. I took long naps morning and evening so I could lie awake all night to see that it wouldn't happen. It couldn't happen. But in the morning the bed would sit there dispassionately soiled and convict me on circumstantial evidence. My punishment was as sure as the tide.

Dad was a compact man, small eyes, small mouth, tight clothes. He was narrow but not mean. For punishment, he locked me in a windowless room and told me to sit still until he came back. It wasn't so bad a punishment, except that when Dad closed the door, the light turned off and I was left there in the dark.

Being four or five, I didn't know any better, so I thought Dad made it dark to add to my punishment. But I learned he didn't know the light went out. It came back on when he unlocked the door. Every time I told him about the light as soon as I could talk again, but he said I was lying.

One day, to prove me a liar, he opened and closed the door a few times from outside. The light winked off and on, off and on, always shining when Dad stuck his head inside. He tried using the door from the inside, and the light stayed on, no matter how hard he slammed the door.

I stayed in the dark longer for lying about the light.

Alone in the dark, I wouldn't have had it so bad if it wasn't for the things that came to me.

They were real to me. They never touched me, but they had a little boy. He looked the way I did in the mirror. They did unpleasant things to him.

Because they were real, I talked about them as if they were real, and I almost earned a bunk in the home for retarded children until I got smart enough to keep the beasts to myself.

My mother hated me. I loved her, of course. I remember her smell mixed up with flowers and cookies and winter fires. I remember she hugged me on my ninth birthday. The trouble came from the notes written in my awkward hand that she found, calling her names I didn't understand. Sometimes there were drawings. I didn't write those notes or make those drawings.

My mother and father must have been glad when I was sent away to reform school after my thirteenth birthday party, the one no one came to.

The reform school was nicer. There were others there who'd had it about like me. We got along. I didn't watch their shifty eyes too much, or ask them what they shifted to see. They didn't talk about my screams at night.

It was home.

My trouble there was that I was always being framed for stealing. I didn't take any of those things they located in my bunk. Stealing wasn't in my line. If you believe any of this at all, you'll see why it couldn't be me who did the stealing.

There was reason for me to steal, if I could have got away with it. The others got money from home to buy the things they needed—razor blades, candy, sticks of tea. I got a letter from Mom or Dad every now and then before they were killed, saying they had sent money or that it was enclosed, but somehow I never got a dime of it.

When I was expelled from reform school, I left with just one idea in mind—to get all the money I could ever use for the things I needed and the things I wanted.

It was two or three years later that I skulked into Brother Partridge's mission on Durbin Street.

The preacher and half a dozen men were singing Onward Christian Soldiers in the meeting room. It was a drafty hall with varnished camp chairs. I shuffled in at the back with my suitcoat collar turned up around my stubbled jaw. I made my hand shaky as I ran it through my knotted hair. Partridge was supposed to think I was just a bum. As an inspiration, I hugged my chest to make him think I was some wino nursing a flask full of Sneaky Pete. All I had there was a piece of copper alloy tubing inside a slice of plastic hose for taking care of myself, rolling sailors and the like. Who had the price of a bottle?

Partridge didn't seem to notice me, but I knew that was an act. I knew people were always watching every move I made. He braced his red-furred hands on the sides of his auctioneer's stand and leaned his splotched eagle beak toward us. "Brothers, this being Thanksgiving, I pray the good Lord that we all are truly thankful for all that we have received. Amen."

Some skin-and-bones character I didn't know struggled out of his seat, amening. I could see he had a lot to be thankful for—somewhere he had received a fix.

"Brothers," Partridge went on after enjoying the interruption with a beaming smile, "you shall all be entitled to a bowl of turkey soup prepared by Sister Partridge, a generous supply of sweet rolls and dinner rolls contributed by the Early Morning Bakery of this city, and all the coffee you can drink. Let us march out to The Stars and Stripes Forever, John Philip Sousa's grand old patriotic song."

I had to laugh at all those bums clattering the chairs in front of me, scampering after water soup and stale bread. As soon as I got cleaned up, I was going to have dinner in a good restaurant, and I was going to order such expensive food and leave such a large tip for the waiter and send one to the chef that they were going to think I was rich, and some executive with some brokerage firm would see me and say to himself, "Hmm, executive material. Just the type we need. I beg your pardon, sir—" just like the razor-blade comic-strip ads in the old magazines that Frankie the Pig sells three for a quarter.

I was marching. Man, was I ever marching, but the secret of it was I was only marking time the way we did in fire drills at the school.

They passed me, every one of them, and marched out of the meeting room into the kitchen. Even Partridge made his way down from the auctioneer's stand like a vulture with a busted wing and darted through his private door.

I was alone, marking time behind the closed half of double doors. One good breath and I raced past the open door and flattened myself to the wall. Crockery was ringing and men were slurping inside. No one had paid any attention to me. That was pretty odd. People usually watch my every move, but a man's luck has to change sometime, doesn't it?

Following the wallboard, I went down the side of the room and behind the last row of chairs, closer, closer, and halfway up the room again to the entrance—the entrance and the little wooden box fastened to the wall beside it.

The box was old and made out of some varnished wood. There was a slot in the top. There wasn't any sign anywhere around it, but you knew it wasn't a mailbox.

My hand went flat on the top of the box. One finger at a time drew up and slipped into the slot. Index, fore, third, little. I put my thumb in my palm and shoved. My hand went in.

There were coins inside. I scooped them up with two fingers and held them fast with the other two. Once I dropped a dime—not a penny, milled edge—and I started to reach for it. No, don't be greedy. I knew I would probably lose my hold on all the coins if I tried for that one. I had all the rest. It felt like about two dollars, or close to it.

Then I found the bill. A neatly folded bill in the box. Somehow I knew all along it would be there.

I tried to read the numbers on the bill with my fingertips, but I couldn't. It had to be a one. Who drops anything but a one into a Skid Row collection box? But still there were tourists, slummers. They might leave a fifty or even a hundred. A hundred!

Yes, it felt new, crisp. It had to be a hundred. A single would be creased or worn.

I pulled my hand out of the box. I tried to pull my hand out of the box.

I knew what the trouble was, of course. I was in a monkey trap. The monkey reaches through the hole for the bait, and when he gets it in his hot little fist, he can't get his hand out. He's too greedy to let go, so he stays there, caught as securely as if he were caged.

I was a man, not a monkey. I knew why I couldn't get my hand out. But I couldn't lose that money, especially that century bill. Calm, I ordered myself. Calm.

The box was fastened to the vertical tongue-and-groove laths of the woodwork, not the wall. It was old lumber, stiffened by a hundred layers of paint since 1908. The paint was as thick and strong as the boards. The box was fastened fast. Six-inch spike nails, I guessed.

Calmly, I flung my whole weight away from the wall. My wrist almost cracked, but there wasn't even a bend in the box. Carefully, I tried to jerk my fist straight up, to pry off the top of the box. It was as if the box had been carved out of one solid piece of timber. It wouldn't go up, down, left or right.

But I kept trying.

While keeping a lookout for Partridge and somebody stepping out of the kitchen for a pull on a bottle, I spotted the clock for the first time, a Western Union clock high up at the back of the hall. Just as I seen it for the first time, the electricity wound the spring motor inside like a chicken having its neck wrung.

The next time I glanced at the clock, it said ten minutes had gone by. My hand still wasn't free and I hadn't budged the box.

"This," Brother Partridge said, "is one of the most profound experiences of my life."

My head hinged until it lined my eyes up with Brother Partridge. The pipe hung heavy in my pocket, but he was too far from me.

"A vision of you at the box projected itself on the crest of my soup," the preacher explained in wonderment.

I nodded. "Swimming right in there with the dead duck."

"Cold turkey," he corrected. "Are you scoffing at a miracle?"

"People are always watching me, Brother," I said. "So now they do it even when they aren't around. I should have known it would come to that."

The pipe was suddenly a weight I wanted off me. I would try robbing a collection box, knowing positively that I would get caught, but I wasn't dumb enough to murder. Somebody, somewhere, would be a witness to it. I had never got away with anything in my life. I was too smart to even try anything but the little things.

"I may be able to help you," Brother Partridge said, "if you have faith and a conscience."

"I've got something better than a conscience," I told him.

Brother Partridge regarded me solemnly. "There must be something special about you, for your apprehension to come through miraculous intervention. But I can't imagine what."

"I always get apprehended somehow, Brother," I said. "I'm pretty special."

"Your name?"

"William Hagle." No sense lying. I had been booked and printed before.

Partridge prodded me with his bony fingers as if making sure I was substantial. "Come. Let's sit down, if you can remove your fist from the money box."

I opened up my fingers and let the coins ring inside the box and I drew out my hand. The bill stuck to the sweat on my fingers and slid out along with the digits. A one, I decided. I had got into trouble for a grubby single. It wasn't any century. I had been kidding myself.

I unfolded the note. Sure enough, it wasn't a hundred-dollar bill, but it was a twenty, and that was almost the same thing to me. I creased it and put it back into the slot.

As long as it stalled off the cops, I'd talk to Partridge.

We took a couple of camp chairs and I told him the story of my life, or most of it. It was hard work on an empty stomach; I wished I'd had some of that turkey soup. Then again I was glad I hadn't. Something always happened to me when I thought back over my life. The same thing.

The men filed out of the kitchen, wiping their chins, and I went right on talking.

After some time Sister Partridge bustled in and snapped on the overhead lights and I kept talking. The brother still hadn't used the phone to call the cops.

"Remarkable," Partridge finally said when I got so hoarse I had to take a break. "One is almost—almost—reminded of Job. William, you are being punished for some great sin. Of that, I'm sure."

"Punished for a sin? But, Brother, I've always had it like this, as long as I can remember. What kind of a sin could I have committed when I was fresh out of my crib?"

"William, all I can tell you is that time means nothing in Heaven. Do you deny the transmigration of souls?"

"Well," I said, "I've had no personal experience—"

"Of course you have, William! Say you don't remember. Say you don't want to remember. But don't say you have no personal experience!"

"And you think I'm being punished for something I did in a previous life?"

He looked at me in disbelief. "What else could it be?"

"I don't know," I confessed. "I certainly haven't done anything that bad in this life."

"William, if you atone for this sin, perhaps the horde of locusts will lift from you."

It wasn't much of a chance, but I was unused to having any at all. I shook off the dizziness of it. "By the Lord Harry, Brother, I'm going to give it a try!" I cried.

"I believe you," Partridge said, surprised at himself.

He ambled over to the money box on the wall. He tapped the bottom lightly and a box with no top slid out of the slightly larger box. He reached in, fished out the bill and presented it to me.

"Perhaps this will help in your atonement," he said.

I crumpled it into my pocket fast. Not meaning to sound ungrateful, I'm pretty sure he hadn't noticed it was a twenty.

And then the bill seemed to lie there, heavy, a lead weight. It would have been different if I had managed to get it out of the box myself. You know how it is.

Money you haven't earned doesn't seem real to you.

There was something I forgot to mention so far. During the year between when I got out of the reformatory and the one when I tried to steal Brother Partridge's money, I killed a man.

It was all an accident, but killing somebody is reason enough to get punished. It didn't have to be a sin in some previous life, you see.

I had gotten my first job in too long, stacking boxes at the freight door of Baysinger's. The drivers unloaded the stuff, but they just dumped it off the truck. An empty rear end was all they wanted. The freight boss told me to stack the boxes inside, neat and not too close together.

I stacked boxes the first day. I stacked more the second. The third day I went outside with my baloney and crackers. It was warm enough even for November.

Two of them, dressed like Harvard seniors, caps and striped duffer jackets, came up to the crate I was dining off.

"Work inside, Jack?" the taller one asked.

"Yeah," I said, chewing.

"What do you do, Jack?" the fatter one asked.

"Stack boxes."

"Got a union card?"

I shook my head.

"Application?"

"No," I said. "I'm just helping out during Christmas."

"You're a scab, buddy," Long-legs said. "Don't you read the papers?"

"I don't like comic strips," I said.

They sighed. I think they hated to do it, but I was bucking the system.

Fats hit me high. Long-legs hit me low. I blew cracker crumbs into their faces. After that, I just let them go. I know how to take a beating. That's one thing I knew.

Then lying there, bleeding to myself, I heard them talking. I heard noises like make an example of him and do something permanent and I squirmed away across the rubbish like a polite mouse.

I made it around a corner of brick and stood up, hurting my knee on a piece of brown-splotched pipe. There were noises on the other angle of the corner and so I tested if the pipe was loose and it was. I closed my eyes and brought the pipe up and then down.

It felt as if I connected, but I was so numb, I wasn't sure until I unscrewed my eyes.

There was a big man in a heavy wool overcoat and gray homburg spread on a damp centerfold from the News. There was a pick-up slip from the warehouse under the fingers of one hand, and somebody had beaten his brains out.

The police figured it was part of some labor dispute, I guess, and they never got to me.

I suppose I was to blame anyway. If I hadn't been alive, if I hadn't been there to get beaten up, it wouldn't have happened. I could see the point in making me suffer for it. There was a lot to be said for looking at it like that. But there was nothing to be said for telling Brother Partridge about the accident, or murder, or whatever had happened that day.

Searching myself after I left Brother Partridge, I finally found a strip of gray adhesive tape on my side, out of the fuzzy area. Making the twenty the size of a thick postage stamp, I peeled back the tape and put the folded bill on the white skin and smoothed the tape back.

There was only one place for me to go now. I headed for the public library. It was only about twenty blocks, but not having had anything to eat since the day before, it enervated me.

The downstairs washroom was where I went first. There was nobody there but an old guy talking urgently to a kid with thick glasses, and somebody building a fix in one of the booths. I could see charred matches dropping down on the floor next to his tennis shoes, and even a few grains of white stuff. But he managed to hold still enough to keep from spilling more from the spoon.

I washed my hands and face, smoothed my hair down, combing it with my fingers. Going over my suit with damp toweling got off a lot of the dirt. I put my collar on the outside of my jacket and creased the wings with my thumbnail so it would look more like a sports shirt. It didn't really. I still looked like a bum, but sort of a neat, non-objectionable bum.

The librarian at the main desk looked sympathetically hostile, or hostilely sympathetic.

"I'd like to get into the stacks, miss," I said, "and see some of the old newspapers."

"Which newspapers?" the old girl asked stiffly.

I thought back. I couldn't remember the exact date. "Ones for the first week in November last year."

"We have the Times microfilmed. I would have to project them for you."

"I didn't want to see the Times," I said, fast. "Don't you have any newspapers on paper?" I didn't want her to see what I wanted to read up on.

"We have the News, bound, for last year."

I nodded. "That's the one I wanted to see."

She sniffed and told me to follow her. I didn't rate a cart to my table, I guess, or else the bound papers weren't supposed to come out of the stacks.

The cases of books, row after row, smelled good. Like old leather and good pipe tobacco. I had been here before. In this world, it's the man with education who makes the money. I had been reading the Funk & Wagnalls Encyclopedia. So far I knew a lot about Mark Antony, Atomic Energy, Boron, Brussels, Catapults, Demons, and Divans.

I guess I had stopped to look around at some of the titles, because the busy librarian said sharply, "Follow me."

I heard my voice say, "A pleasure. What about after work?"

I didn't say it, but I was used to my voice independently saying things. Her neck got to flaming, but she walked stiffly ahead. She didn't say anything. She must be awful mad, I decided. But then I got the idea she was flushed with pleasure. I'm pretty ugly and I looked like a bum, but I was young. You had to grant me that.

She waved a hand at the rows of bound News and left me alone with them. I wasn't sure if I was allowed to hunt up a table to lay the books on or not, so I took the volume for last year and laid it on the floor. That was the cleanest floor I ever saw.

It didn't take me long to find the story. The victim was a big man, because the story was on the second page of the Nov. 4 edition.

I started to tear the page out, then only memorized the name and home address. Somebody was sure to see me and I couldn't risk trouble just now.

I stuck the book back in line and left by the side door.

I went to a dry-cleaner, not the cheapest place I knew, because I wouldn't be safe with the change from a twenty in that neighborhood. My suit was cleaned while I waited. I paid a little extra and had it mended. Funny thing about a suit—it's almost never completely shot unless you just have it ripped off you or burned up. It wasn't exactly in style, but some rich executives wore suits out of style that they had paid a lot of money for. I remembered Fredric March's double-breasted in Executive Suite while Walter Pidgeon and the rest wore Ivy Leagues. Maybe I would look like an eccentric executive.

I bought a new shirt, a good used pair of shoes, and a dime pack of single-edged razor blades. I didn't have a razor, but anybody with nerve can shave with a single-edge blade and soap and water.

The clerk took my two bucks in advance and I went up to my room.

I washed out my socks and underwear, took a bath, shaved and trimmed my hair and nails with the razor blade. With some soap on my finger, I scrubbed my teeth. Finally I got dressed.

Everything was all right except that I didn't have a tie. They had them, a quarter a piece, where I got the shoes. It was only six blocks—I could go back. But I didn't want to wait. I wanted to complete the picture.

The razor blade sliced through the pink bath towel evenly. I cut out a nice modern-style tie, narrow, with some horizontal stripes down at the bottom. I made a tight, thin knot. It looked pretty good.

I was ready to leave, so I started for the door. I went back. I had almost forgotten my luggage. The box still had three unwrapped blades in it. I pocketed it. I hefted the used blade, dulled by all the work it had done. You can run being economical into stinginess. I tossed it into the wastebasket.

I had five hamburgers and five cups of coffee. I couldn't finish all of the French fries.

"Mac," I said to the fat counterman, who looked like all fat countermen, "give me a Milwaukee beer."

He stopped polishing the counter in front of his friend. "Milwaukee, Wisconsin, or Milwaukee, Oregon?"

"Wisconsin."

He didn't argue.

It was cold and bitter. All beer is bitter, no matter what they say on TV. I like beer. I like the bitterness of it.

It felt like another, but I checked myself. I needed a clear head. I thought about going back to the hotel for some sleep; I still had the key in my pocket (I wasn't trusting it to any clerk). No, I had had sleep on Thanksgiving, bracing up for trying the lift at Brother Partridge's. Let's see, it was daylight outside again, so this was the day after Thanksgiving. But it had only been sixteen or twenty hours since I had slept. That was enough.

I left the money on the counter for the hamburgers and coffee and the beer. There was $7.68 left.

As I passed the counterman's friend on his stool, my voice said, "I think you're yellow."

He turned slowly, his jaw moving further away from his brain.

I winked. "It was just a bet for me to say that to you. I won two bucks. Half of it is yours." I held out the bill to him.

His paw closed over the money and punched me on the biceps. Too hard. He winked back. "It's okay."

I rubbed my shoulder, marching off fast, and I counted my money. With my luck, I might have given the counterman's friend the five instead of one of the singles. But I hadn't. I now had $6.68 left.

"I still think you're yellow," my voice said.

It was my voice, but it didn't come from me. There were no words, no feeling of words in my throat. It just came out of the air the way it always did.

I ran.

Harold R. Thompkins, 49, vice-president of Baysinger's, was found dead behind the store last night. His skull had been crushed by a vicious beating with a heavy implement, Coroner McClain announced in preliminary verdict. Tompkins, who resided at 1467 Claremont, Edgeway, had been active in seeking labor-management peace in the recent difficulties....

I had read that a year before. The car cards on the clanking subway and the rumbling bus didn't seem nearly so interesting to me. Outside the van, a tasteful sign announced the limits of the village of Edgeway, and back inside, the monsters of my boyhood went bloomp at me.

I hadn't seen anything like them in years.

The slimy, scaly beasts were slithering over the newspaper holders, the ad card readers, the girl watchers as the neat little carbon-copy modern homes breezed past the windows.

I ignored the devils and concentrated on reading the withered, washed-out political posters on the telephone poles. My neck ached from holding it so stiff, staring out through the glass. More than that, I could feel the jabberwocks staring at me. You know how it is. You can feel a stare with the back of your neck and between your eyes. They got one brush of a gaze out of me.

The things abruptly started their business, trying to act casually as if they hadn't been waiting for me to look at them at all. They had a little human being of some sort.

It was the size of a small boy, like the small boy who looked like me that they used to destroy when I was locked up with them in the dark. Except this was a man, scaled down to child's size. He had sort of an ugly, worried, tired, stupid look and he wore a shiny suit with a piece of a welcome mat or something for a necktie. Yeah, it was me. I really knew it all the time.

They began doing things to the midget me. I didn't even lift an eyebrow. They couldn't do anything worse to the small man than they had done to the young boy. It was sort of nostalgic watching them, but I really got bored with all that violence and killing and killing the same kill over and over. Like watching the Saturday night string of westerns in a bar.

The sunlight through the window was yellow and hot. After a time, I began to dose.

The shrieks woke me up.

For the first time, I could hear the shrieks of the monster's victim and listen to their obscene droolings. For the very first time in my life. Always before it had been all pantomime, like Charlie Chaplin. Now I heard the sounds of it all.

They say it's a bad sign when you start hearing voices.

I nearly panicked, but I held myself in the seat and forced myself to be rational about it. My own voice was always saying things everybody could hear but which I didn't say. It wasn't any worse to be the only one who could hear other things I never said. I was as sane as I ever was. There was no doubt about that.

But a new thought suddenly impressed itself on me.

Whatever was punishing me for my sin was determined that I turn back before reaching 1467 Claremont.

"Clrmnt," the driver announced, sending the doors hissing open and the bus cranking to a stop.

I walked through the gibbering monsters, and passing the driver's seat, I heard my voice say, "Don't splatter me by starting up too soon, fat gut."

The driver looked at me with round eyes. "No, sir, I won't."

The monsters gave it up and stopped existing.

The bus didn't start until I was halfway up the block of sandine moderns and desk-size patios.

Number 1423 was different from the other houses. It was on fire.

One of the most beautiful women I've ever seen came running up to me. What black hair, what red lips, what sparkling eyes she had when I finally got up that far! "Sir," she said, "my baby brother is in there. I'd be so grateful—"

I grabbed for her. My hand went right on through. I didn't try grabbing her again. This time, I had a feeling I would feel her. I didn't want to be that bad off.

I walked on, ignoring the flames shooting out of 1423.

As I reached the patio of 1467, the flames stopped. It was a queer kind of break. No fadeout, just a stoppage. I took a step backward. No flames this time, but the very worst and very biggest monster of them all. Coming suddenly like that, it got to my spine and stomach, even though I was pretty used to them. I stepped away from it and it was gone.

Number 1467 was different from the other houses, and it wasn't even on fire. It was on two lots, and it had two picture windows, but only one little porch and front door. I guess even the well-to-do have a hard time finding big houses and good building sites and the right neighborhood. The trouble is so many people are well-to-do and there just aren't enough old manses to go around.

I strolled up the stucco path and lifted the wrought-iron knocker, which rang a bell.

The door opened and there was a girl there. She wasn't much compared to the one I put my hand through. But she was all right—brown hair, a nice face underneath the current shades of cosmetics, no figure for a stripper, but it would pass.

"You the maid?" I inquired.

"I am Miss Tompkins," she said.

"Oh. Any relation to Harold J. Tompkins?"

"My father. He died last year."

"Can I see your mother?"

"Mother died a few months after Daddy did."

"You'll do then."

I stepped inside. Miss Tompkins seemed too surprised to protest.

"I'm William Hagle," I said. "I want to help you."

"Mr. Hagle, whatever it is—insurance—"

"That's not it exactly," I told her. "I just want to help you. I only want to do whatever you want me to do."

She stared at me, her eyes moving too quickly over my face. "I've never even seen you before, have I? Why do you want to help me? How?"

"What's so damned hard to understand? I just want to help. I don't have any money, but I can work and give you my pay. You want me to clean up the basement, the yard? Got any painting to be done? Hell, I can even sew. Anything—don't you understand—I'll do anything for you."

The girl was breathing too hard now. "Mr. Hagle, if you're hungry, I can find something—no, I don't think there is anything. But I can give you some money to—"

"Damn it, I don't want your money! Here, I'll give you mine!" I wadded up the $6.38 cents I had left, plus one bus transfer, and put it on the top of a little bookcase next to the door. "I know it doesn't mean anything to you, but it's every penny I've got. Can't I do anything for you? Empty the garbage—"

"We have a disposal," she said automatically.

"Scrub the floors."

"There's a polisher in the closet."

"Make the beds!" I yelled. "You don't have a machine for that, do you?"

The corners of Miss Tompkins' eyes drew up and the corners of her mouth drew down. She stayed like that for a full second, then smiled a strange smile. "You—you saw me on the street." She was breathing her words now, so softly that I could only just understand them. "You thought I was—stacked."

"To tell the truth, ma'am, you aren't so—"

"Well, sit down. Don't go away. I'll just go into the next room—slip into something comfortable—"

"Miss Tompkins!" I grabbed hold of her. She felt real. I hoped she was. "I want nothing from you. Nothing! I only want to do something for you, anything for you. I've got to help you, can't you understand? I KILLED YOUR FATHER."

I hadn't meant to tell her that, of course.

She screamed and began twisting and clawing the way I knew she would as soon as I said it. But she stopped, stunned, as if I'd slapped her out of hysterics, only I'd never let go of her shoulders.

She hung then, her face empty, repeating, "What? What?"

Finally she began laughing and she pulled away from me so gently and naturally that I had to let go. She sank down and sat on top of my money on the little bookcase. She laughed some more into her two open hands.

I stood there, not knowing what to do with myself.

She looked up at me and brushed away a few tears with her fingertips. "You want to get me off of your conscience, do you, William Hagle? God, that's a good one." She reached out and took my hand in hers. "Come along down into the basement, William. I want to show you something. Afterward, if you want to—if you really want to—you may kill me."

"Thanks," I said.

I couldn't think of anything else to say.

Down in the basement, the machinery looked complex, with all sorts of thermostats and speedometers.

"Automatic stoker?" I asked.

"Time machine," she said.

"You don't mean a time machine like H. G. Wells's," I said, to show her I wasn't ignorant.

"Not exactly like that, but close," she answered sadly. "This has been the cause of all your trouble, William."

"It has?"

"Yes. This house and the ground around it are the Primary Focus area for the Hexers. The Hexers have tormented and persecuted you all your life. They got you into trouble. They made you think you were going crazy—"

"I never thought I was going crazy!" I yelled at her.

"That must have made it worse," she said miserably.

I thought about it. "I suppose it did. What are the Hexers? What—for the sake of argument—have they got against me?"

"The Hexers aren't human. I suppose they are extraterrestrials. No one ever told me. Maybe they are a kind of human strain that went different. I don't really know. They want different things than we do, but they can buy some of them with money, so they can be hired. People in the future hire them to hex people in the past."

"Why would anybody up ahead there with Buck Rogers want to cause me trouble? I'm dead then, aren't I?"

"Yes, you must be. It's a long time into the future. But, you see, some of my relatives there want to punish you for—it must be for killing Father. They lost out on a chain of inheritance because he died when he did. They have money now, but they are bitter because they had to make it themselves. They can afford every luxury—even the luxury of revenge."

I suppose when you keep seeing monsters and hearing yourself say things you didn't say, you can believe unusual things easier. I believed Miss Tompkins.

"It was not murder," I said. "I killed him by accident."

"No matter. They would hex you if you had hit him with a car in a fog or given him the flu by sneezing in his face. I understand people are hexed all the time for things they never even knew they did. People up there have a lot of leisure, a lot of time to indulge their every irritation or hate. I think it must be decadent, the way Rome was."

"What do you—and the machine—have to do with my hex?" I asked.

"This is the Primary Focus area, I told you. It's how the Hexers get into this time hypothesis. They can't get back into this Primary itself, but they can come and go through the outer boundary. It's hard to set up a Primary Focus—takes a tremendous drain of power. They broke through into the basement of the old house before I was born and Daddy was the first custodian of the machine. He never knew that he was helping avenge his own death. They let that slip later, after—it happened."

"Why did they come to you? Why did you help them?"

She turned half away. "The custodian is well paid. My relatives preferred the salary to go to someone in the family, instead of an outsider. Daddy accepted the offer and I've carried on the job."

"Paid? You were paid?"

She brushed at her eyes. "Oh, not in United States currency. But—Daddy got to be president of the store. It was set up so he could make a fortune that they could inherit. All he left was his insurance, and that went to mother. She died a few months later and some of it went to me and the rest to her relatives."

"You mean my life has been like it has because some descendants of yours in the future hate me for an accident that deprived them of some money?"

She nodded enthusiastically. "You understand! And because I helped the Hexers they hired get to you. I was afraid you wouldn't believe me. Now"—she stopped to exhale—"do you want to kill me?"

"No, I don't want to kill you." I walked over and squinted at the machine. "Could I get into the future with this thing?"

"I don't know how you work the outer boundary. I think you need something else. There's an internal energy contact—you can talk to Communications." She raced through that. "You want to kill them, don't you? The Hexers and my relatives?"

"I don't want to kill anybody," I told her patiently. "I feel dirty just hearing how far some people can go for revenge. I just want them to let me alone. Why don't they kill me and get it over with?"

"They haven't a license to kill. Not yet. There's legislation going on."

"Listen," I said, listening to the idea coming into my head, "listen. These descendants of your mother's relatives—they did inherit money because your father died. Maybe they feel grateful to me. Maybe they would help me. Would you help me try to talk to them?"

"Yes," Miss Tompkins said, and she used a dial on the machine.

It was as simple as putting through a phone call.

"We really understand your situation," Mr. Grimes-Tompkins said. "But it would take quite a bit to buy off the Hexers. However, we certainly appreciate the killing you made for us."

"Couldn't you buy off the Hexers, then, with some of the money I brought to your side of the family?" I asked.

"We don't appreciate it that much."

"What? You aren't going to pay him back for killing my father?" Miss Tompkins cried, outraged.

"Look," I said, "if you had some money of mine, would you pay off the Hexers for me? You do still use money up there, don't you?"

"We certainly do, young man. Just what did you have in mind?"

"If I gave you authorization now to use any assets I have in your time, would it be legal?"

"Declarations by temporal transmission? Yes, of course. Routine transaction."

"Take any money I have and use it to pay off the Hexers. Will you do it?"

"I don't see why not, since our ancestor seems to approve."

Miss Tompkins regarded me solemnly. "What do you intend to do, William?"

"Banks are out," I said, thinking hard. "They don't let inactive accounts go on drawing interest more than twenty years, or something like that. But government bonds don't have to be converted when they mature. One bond can pile up a fantastic amount of interest for them to collect."

"You have government bonds, William?"

"Not yet."

Miss Tompkins stood close to me. "I have plenty of money, William. I'll give it to you. You can buy bonds in my name."

"No. I'll get my own money."

"Shall I destroy the machine, William? Of course they'll only open another Focus—"

"No, you would just get yourself hexed too."

"What can I do, William?" she asked. "All along, ever since I was a little girl, I've known I've been helping to torture somebody. I didn't even know your name, William, but I helped torture you—"

"Because I killed your father."

"—and I've got to make it up to you. I'll give you everything, William, everything."

"Sure," I said, "to take me off your conscience. And if I take your offer and you get hexed, what happens to my conscience? Do we go around again—me working my tail off to raise the dough to get you unhexed, and you buying the Hexers off me? Where would it stop? We're even right now. Let's let it go at that."

"But, William, if we've taken, now we can give to each other."

She looked almost pretty then, and I wanted her the way I'd always wanted women. But I knew better. She wasn't going to get me into any trouble.

"No, thanks. Good-by."

I walked away from her.

For the first time, I could see what my life would be like if I wasn't hexed. Now I could realize that I knew how to do things right if I was only let alone.

The intern took the blood smear. He reeled off a long string of questions about diseases I wasn't allowed to have.

"No," I said, "and I haven't given blood in the last thirty days."

He took my sample of blood and left.

I had to have eighteen dollars and seventy-five cents. They paid you twenty dollars a pint for blood here.

One government bond held for centuries would pile up a fortune in interest. The smallest bond you can buy is twenty-five dollars face value, and it costs eighteen seventy-five.

If I had kept that twenty, I would have had a buck and a quarter change. But if I hadn't have gotten cleaned up, the hospital might not have accepted me as a donor at all. They had had some bad experiences from old bums dying from giving too often.

I only hoped I could force myself to let that bond go uncashed through the rest of my life.

The intern returned, his small mustache now pointing down. "Mr. Hagle, I have some bad news for you. Very bad. I hardly know how to tell you, but—you've got lukemia."

I nodded. "That means you won't take my blood." Maybe it also meant that I would never be allowed to have eighteen dollars and seventy-five cents in one lump again as long as I lived.

"No," the intern finally managed. "We can't accept your blood—"

I waved him off. "Isn't there some fund to take care of lukemia victims? Feed them, house them, send them to Florida to soak up the sun?"

"Certainly there is such a fund, and you may apply, Mr. Hagle."

"I'd certainly benefit a lot from that fund. Doctor, humor me. Test me again and see if I still have lukemia."

He did. I didn't.

"I don't understand this," the intern said, looking frightened. "Transitory lukemia? It must be a lab error."

"Will you buy my blood now?"

"I'm afraid as long as there is some doubt—this must be something new."

"I suppose it is," I told him. "I have all sorts of interesting symptoms."

"You do?" The intern was vitally interested. "Feel free to tell me all about them."

"I see and hear things."

"Really?"

"Do you believe in ESP?"

"I've sometimes wondered."

"Test me as much as you like. You'll find that in any game of chance, I score consistently far below the level of wins I should get by the law of averages. I'm psionically subnormal. And that's just the beginning."

"This must be really new," the intern said, eyes shining.

"It is," I assured him. "And listen, Doctor, you don't want to turn something like me over to your superiors, to leave me to the mercies of the A.M.A. This can be big, Doctor, big."

They offered Hagle's Disease to a lot of comedians, but finally it was the new guy, Biff Kelsey, that got it and made it his own. He did a thirty-hour telethon for Hagle's Disease.

Things really started to roll then. Boston coughed up three hundred thousand alone. The most touching contribution came from Carrville.

I plugged away on the employ-the-physically-handicapped theme and was made president of the Foundation for the Treatment of Hagle's Disease. Dr. Wise (the intern) was the director.

So far, I had been living soft at Cedars, but I hadn't got my hands on one red cent. I wanted to get that government bond to buy off the Hexers, but at the same time it no longer seemed so urgent. They seemed to have given up, and were just sitting back waiting for their bribe.

One morning three months later, Doc Wise came worriedly into my room at the hospital.

"I don't like these reports, William," he said. "They all say there's nothing wrong with you."

"It comes and it goes," I said casually. "You saw some of the times when it came."

"Yes, but I'm having trouble convincing the trustees you weren't malingering. And, contrary to our expectations, no one else in the country seems to have developed Hagle's Disease."

"Stop worrying, Doc. Read the Foundation's charter. You have to treat Hagle's Disease, which means you can use that money to treat any disease of mine while we draw our salaries. I must have something wrong with me."

Wise shook his head. "Nothing. Not even dandruff or B.O. You are the healthiest man I have ever examined. It's unnatural."

Six months afterward, I had been walking all night in the park, in the rain. I hadn't had anything to eat recently and I had fever and I began sneezing. The money was still in the bank—no, not in my name—I couldn't touch it; Miss Tompkins' descendants couldn't touch it—just waiting for me to—

I started running toward the hospital.

I slammed my fists against Wise's door. "Obed up, Wise. Id's be, Hagle. I god a cold. That's a disease, is'd it?"

Wise threw back the door. "What did you say?"

"I said 'Open up, Wise. It's me, Hagle. I've got a cold'.... Never mind, Wise, never mind."

But you don't want to hear about all that. You want to know about what happened in the relief office. There's not much to tell.

I picked up the check from the guy's desk and looked at it. Nine fifty-seven to buy food for two weeks. I griped that it wasn't enough—not enough to keep alive on and save eighteen seventy-five clear in a lifetime.

The slob at the desk said, "What have you got to complain about? You got your health, don't you?"

That's when I slugged him and smashed up the relief office, and that's why the four cops dragged me here, and that's why I'm lying here on your couch telling you this story, Dr. Schultz.

I had my health, sure, but I finally figured out why. If you believe any of this, you're thinking that the Hexers must have laid off me, which is why I'm healthy. I thought so too, but how would that add up?

Look, I tried every way I could to raise eighteen seventy-five to buy a government bond. I never made it I never made it because I wasn't allowed to.

But I didn't know it because I'd been euchred into the Foundation for the Treatment of Hagle's Disease. Hundreds of thousands of dollars, all earmarked for one purpose only—treating my disease—and I haven't got any!

Or maybe you're figuring the way I did, that senility is a disease, and all I have to do is wait for it to creep up on me so I can get some of that Foundation money. But the Hexers have that fixed too, I'll bet. I'm not sure, but I think I'm going to live for centuries without a sick day in my life. In other words, I'm going to live that life out as poor as I am right now!

It's a fantastic story, Doctor, but you believe me, don't you? You do believe every word of it. You have to, Doctor!

Because a persecution complex is kind of a disease and I'd have to be treated for it.

Now will you let me out of this jacket so I can smoke a cigarette?